I learned to touch type on a manual typewriter when I was about 10 or 11. I guess that was my first experience with fonts — I didn’t know that then but I remember liking that my typewritten sheets looked neat and tidy, as opposed to my crooked and messy handwritten reports. As a freshman in college, I worked in the computer center, where they had one of the first laser printers. I was envious of the graduate students using it for their papers and even computer program listings — they no longer had just fixed-width Courier at their disposal, they had beautiful Times!

I learned to touch type on a manual typewriter when I was about 10 or 11. I guess that was my first experience with fonts — I didn’t know that then but I remember liking that my typewritten sheets looked neat and tidy, as opposed to my crooked and messy handwritten reports. As a freshman in college, I worked in the computer center, where they had one of the first laser printers. I was envious of the graduate students using it for their papers and even computer program listings — they no longer had just fixed-width Courier at their disposal, they had beautiful Times!

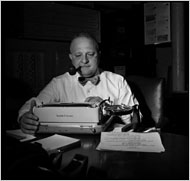

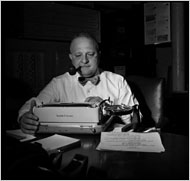

But back to typewriters… I read with interest an obituary in the NY Times the other morning: “Martin K. Tytell, Typewriter Wizard, Dies at 94.” From the obituary:

But back to typewriters… I read with interest an obituary in the NY Times the other morning: “Martin K. Tytell, Typewriter Wizard, Dies at 94.” From the obituary:

| Martin Tytell, whose unmatched knowledge of typewriters was a boon to American spies during World War II, a tool for the defense lawyers for Alger Hiss, and a necessity for literary luminaries and perhaps tens of thousands of everyday scriveners who asked him to keep their Royals, Underwoods, Olivettis (and their computer-resistant pride) intact, died on Thursday in the Bronx. He was 94….

He made a hieroglyphics typewriter for a museum curator, and typewriters with musical notes for musicians. He adapted keyboards for amputees and other wounded veterans. He invented a reverse-carriage device that enabled him to work in right-to-left languages like Arabic and Hebrew. An error he made on a Burmese typewriter, inserting a character upside down, became a standard, even in Burma….

Mr. Tytell was proud of the rarity of his expertise, and relished the eccentric nature of his business. “We don’t get normal people here,” he said of his shop. And he was aware that his connection to the typewriter bordered on love.

“I’m 83 years old and I just signed a 10-year lease on this office; I’m an optimist, obviously,” Mr. Tytell told the writer Ian Frazier in a 1997 article in The Atlantic Monthly, commenting on the likelihood that typewriters weren’t going to last in the world much longer. “I hope they do survive — manual typewriters are where my heart is. They’re what keep me alive.”

Don’t miss Ian Frazier’s article about his search to fix the errant “e” on his beloved manual typewriter that lead him to Tytell — it’s a wonderful read. At the end, Mr. Tytell says:

“What’s so intriguing about a manual typewriter is that it’s all right there in front of you — all the thought that went into it, all these really smart guys that worked on it and gave their lives for it. The way these machines continue to function, it really is a miracle. You see some old beat-up machine in an attic or someplace and you touch the keys and it still works fine. Companies still make typewriter ribbons — the dry-goods business is as strong as ever — so obviously somebody’s still using them. Like in the war, nobody was making typewriters, but people kept on using them anyway. A little bit of maintenance and regular use and you can keep a typewriter running a long time. These other machines, computers and so on, even electric typewriters, they have a soul that’s hooked into the wall. A manual typewriter has a soul that doesn’t need anything else in order to exist — it exists in itself. People are always going to like that about a manual.”

(The photo above is by Patrick Burns for the NY Times.)

After reading People of the Book, I’ve been looking for more fiction that features books and bookmaking. My friend Sharon suggested Robert Hellenga’s 1995 book The Sixteen Pleasures, about a 29 year old midwestern American, Margot, who is trained as a book conservator and goes to Florence in 1966 when the Arno flooded and destroyed or damaged millions of books and other artwork. Ostensibly she goes to Italy to help repair and protect the books, but she’s really in search of adventure and the memory of living in Florence as a teenager. She ends up staying at an abbey of cloistered nuns and one day a nun comes upon a pornographic volume bound with a prayer book that has been damaged by the flood. It turns out to be the only copy of long lost erotic sonnets, accompanied by rather anatomically explicit engravings. The abbess asks Margot to take care of the book and sell it, to help the abbey (but to be sure the Church doesn’t find out about it). So Margot rebinds the folios and repairs the spine and covers and goes about trying to sell the book. In the meantime, there’s lots of fine detail about the restoration as well as wonderful passages about art and the life of Florence. Plus Margot finds lots of romance and adventure. After reading People of the Book, I’ve been looking for more fiction that features books and bookmaking. My friend Sharon suggested Robert Hellenga’s 1995 book The Sixteen Pleasures, about a 29 year old midwestern American, Margot, who is trained as a book conservator and goes to Florence in 1966 when the Arno flooded and destroyed or damaged millions of books and other artwork. Ostensibly she goes to Italy to help repair and protect the books, but she’s really in search of adventure and the memory of living in Florence as a teenager. She ends up staying at an abbey of cloistered nuns and one day a nun comes upon a pornographic volume bound with a prayer book that has been damaged by the flood. It turns out to be the only copy of long lost erotic sonnets, accompanied by rather anatomically explicit engravings. The abbess asks Margot to take care of the book and sell it, to help the abbey (but to be sure the Church doesn’t find out about it). So Margot rebinds the folios and repairs the spine and covers and goes about trying to sell the book. In the meantime, there’s lots of fine detail about the restoration as well as wonderful passages about art and the life of Florence. Plus Margot finds lots of romance and adventure.

The book was a good read. And I quickly discovered that Hellenga recently wrote another book about Margot, The Italian Lover — I always want to know what happens to the characters in the books I’ve enjoyed. “The Italian Lover” takes place in 1990, Margot is now 53 and still living in Italy, still restoring books. The conceit in the new novel is that Margot wrote a book called “The Sixteen Pleasures” about her life and it is to be made into a film. While Margot is still (mostly) front and center, and there’s a bit of book restoration, there are many more characters in the new novel and a lot of plot about making movies. Worse are the annoying product placements (not just an espresso maker, an Alessi espresso maker). Oh well, I did enjoy finding out more about Margot’s life. The book was a good read. And I quickly discovered that Hellenga recently wrote another book about Margot, The Italian Lover — I always want to know what happens to the characters in the books I’ve enjoyed. “The Italian Lover” takes place in 1990, Margot is now 53 and still living in Italy, still restoring books. The conceit in the new novel is that Margot wrote a book called “The Sixteen Pleasures” about her life and it is to be made into a film. While Margot is still (mostly) front and center, and there’s a bit of book restoration, there are many more characters in the new novel and a lot of plot about making movies. Worse are the annoying product placements (not just an espresso maker, an Alessi espresso maker). Oh well, I did enjoy finding out more about Margot’s life.

|