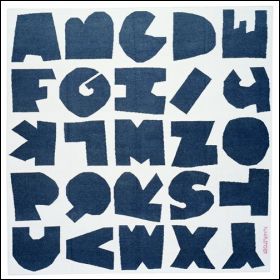

There’s not much of description (or a price) for this alphabet rug by Alan Fletcher, other than it’s subtitled “paper cutout alphabet rug,” but it’s awfully cheery and playful. See what there is to say about it here. There’s not much of description (or a price) for this alphabet rug by Alan Fletcher, other than it’s subtitled “paper cutout alphabet rug,” but it’s awfully cheery and playful. See what there is to say about it here.

|

There’s not much of description (or a price) for this alphabet rug by Alan Fletcher, other than it’s subtitled “paper cutout alphabet rug,” but it’s awfully cheery and playful. See what there is to say about it here. There’s not much of description (or a price) for this alphabet rug by Alan Fletcher, other than it’s subtitled “paper cutout alphabet rug,” but it’s awfully cheery and playful. See what there is to say about it here.

|

In 1999 my mother-in-law gave me several old perfume bottles, mostly figurines. All from the early 20th century, they are wonderful to look at. As I found out more about them, I got hooked and added to the collection. In a few years I had a shelf-full and decided that was enough. That’s one of mine to the right — a crowntop kewpie doll perfume bottle from the 1930s. Sadly last month she got knocked off her shelf and broke. My husband glued her back together but should I replace her?

In 1999 my mother-in-law gave me several old perfume bottles, mostly figurines. All from the early 20th century, they are wonderful to look at. As I found out more about them, I got hooked and added to the collection. In a few years I had a shelf-full and decided that was enough. That’s one of mine to the right — a crowntop kewpie doll perfume bottle from the 1930s. Sadly last month she got knocked off her shelf and broke. My husband glued her back together but should I replace her?

![]() Then the other day I saw this obituary in the NY Times. It’s about a book collector and says in part:

Then the other day I saw this obituary in the NY Times. It’s about a book collector and says in part:

All the collectors I know keep on collecting, sometimes replacing one collectable with another when they are done with one habit, just like Mr. Friedlaender. I never gave much thought to why I decided to stop collecting perfume bottles — but I have kept collecting. I replaced bottles with my small and still growing collection of artist’s books.

![]() But what to do with my kewpie doll? My collection is modest, with nice but not stellar examples. On the “do it” side of the argument: My bottles make me happy and sit in a prominent place in my office. They are so much easier to display than books — what’s interesting about them is all up front (most of my bottles are empty, so the scent that should be hidden under the stopper isn’t). On the “don’t do it” side: She’ll be pricey (for me) and hard to replace. And how much is my collection just a pleasure to look at, or a more serious endeavor? I’ve already taken a look at my bottles to re-evaluate what I have, in a way I haven’t looked at them in quite some time.

But what to do with my kewpie doll? My collection is modest, with nice but not stellar examples. On the “do it” side of the argument: My bottles make me happy and sit in a prominent place in my office. They are so much easier to display than books — what’s interesting about them is all up front (most of my bottles are empty, so the scent that should be hidden under the stopper isn’t). On the “don’t do it” side: She’ll be pricey (for me) and hard to replace. And how much is my collection just a pleasure to look at, or a more serious endeavor? I’ve already taken a look at my bottles to re-evaluate what I have, in a way I haven’t looked at them in quite some time.

![]() The article about Mr. Friedlaender got me to look at my artist’s book collection with a new eye too, and before I replace my kewpie, the current habit needs tending. Another book as my Christmas present to myself would be just the thing!

The article about Mr. Friedlaender got me to look at my artist’s book collection with a new eye too, and before I replace my kewpie, the current habit needs tending. Another book as my Christmas present to myself would be just the thing!

|

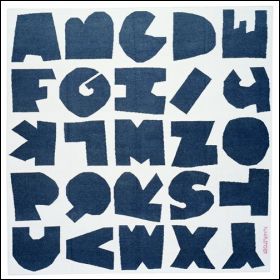

One of the first books on making books I ever bought was Shereen LaPlantz’s Cover to Cover. I still refer to it — and share it — especially when someone newish to bookmaking asks me about making a book for a particular purpose. The instructions and diagrams are clear and there are lots of photos of finished examples. |

The short version: Archimedes is considered one of the greatest mathematicians of all time. He died in 212 BC. He wrote his thoughts and proofs in Greek on papyrus rolls and sent them as letters to other mathematicians. Over time these ideas were preserved both by being translated (into Latin and Arabic) and rewritten (by scribes into the codex book form). Little of the Greek original remains today, in any form, and much of what he wrote is presumed lost. One rare codex that contains the original Greek is the The Archimedes Palimpsest. A palimpsest is a parchment text where the writing has been partially or completely erased and another text written over it. The Archimedes Palimpsest outwardly looks like a medieval prayer book from the 13th century, the text that was erased and overwritten by the prayers is a transcription of several of Archimedes’ letters. The book is in horrible shape — full of mold, with pages lost or cut out, and very bad mending. In 1998 an anonymous collector bought the book and since then it has gone through another transformation — conservation and digital imaging to allow scholars to read Archimedes’ text. The Archimedes Codex tells the story of the codex and what was found in reading the texts.

The short version: Archimedes is considered one of the greatest mathematicians of all time. He died in 212 BC. He wrote his thoughts and proofs in Greek on papyrus rolls and sent them as letters to other mathematicians. Over time these ideas were preserved both by being translated (into Latin and Arabic) and rewritten (by scribes into the codex book form). Little of the Greek original remains today, in any form, and much of what he wrote is presumed lost. One rare codex that contains the original Greek is the The Archimedes Palimpsest. A palimpsest is a parchment text where the writing has been partially or completely erased and another text written over it. The Archimedes Palimpsest outwardly looks like a medieval prayer book from the 13th century, the text that was erased and overwritten by the prayers is a transcription of several of Archimedes’ letters. The book is in horrible shape — full of mold, with pages lost or cut out, and very bad mending. In 1998 an anonymous collector bought the book and since then it has gone through another transformation — conservation and digital imaging to allow scholars to read Archimedes’ text. The Archimedes Codex tells the story of the codex and what was found in reading the texts.

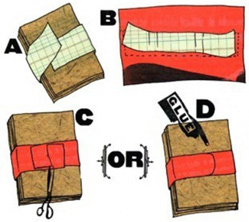

![]() The chapters in the book alternate between the story of the physical object and the story of reading the texts contained in the codex. My original interest was in the conservation effort, and while there’s certainly a lot of that, I got much more. For example there’s a discussion of the “technology changes” in reading and writing between third century BC and now. Archimedes wrote in uppercase Greek with no word spaces — just thinking about reading an all uppercase text gives me a headache, so I can’t imagine reading something with no word spaces. Conserving the book also meant taking pictures of the pages, and if possible, making the underlying Archimedes text legible. The second half of the book details that effort, which surprisingly involved using Stanford’s linear accelerator to image and get to some of the text that was covered over by thick layers of paint. The photo at the upper left shows one page of the book, with a diagram from Archimedes showing up faintly in the background. To the right you can see the Greek under the Latin prayer text and pointing hand.

The chapters in the book alternate between the story of the physical object and the story of reading the texts contained in the codex. My original interest was in the conservation effort, and while there’s certainly a lot of that, I got much more. For example there’s a discussion of the “technology changes” in reading and writing between third century BC and now. Archimedes wrote in uppercase Greek with no word spaces — just thinking about reading an all uppercase text gives me a headache, so I can’t imagine reading something with no word spaces. Conserving the book also meant taking pictures of the pages, and if possible, making the underlying Archimedes text legible. The second half of the book details that effort, which surprisingly involved using Stanford’s linear accelerator to image and get to some of the text that was covered over by thick layers of paint. The photo at the upper left shows one page of the book, with a diagram from Archimedes showing up faintly in the background. To the right you can see the Greek under the Latin prayer text and pointing hand.

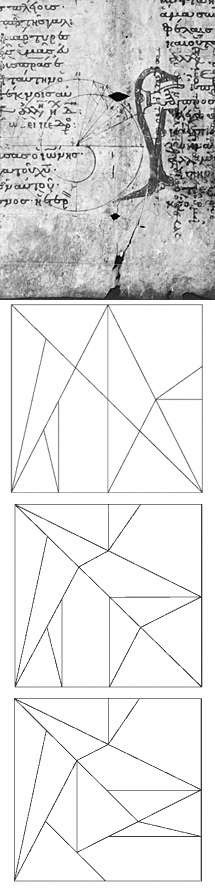

![]() The alternating chapters tell what was found in the texts and how they were read and interpreted. Here’s where I got my biggest surprise. I majored in math in college, but that was a long time ago and I’ve forgotten most of what I learned. Calculus and even geometry just aren’t something I use in my current every-day life. In these chapters, the authors work though some of Archimedes’ logic and proofs. At first I thought I’d just skim or skip them, but found myself drawn in, working carefully through the text, and remembering doing the same thing as a student. And I was quite captivated by the “stomachion,” a puzzle that Archimedes talks about where the 14 shapes in the first square to the left are rearranged to make another square (the next 2 squares are rearrangments; Archimedes wanted to know how many such rearrangements there are). I found the design really pleasing to look at. You can see all the permutations here.

The alternating chapters tell what was found in the texts and how they were read and interpreted. Here’s where I got my biggest surprise. I majored in math in college, but that was a long time ago and I’ve forgotten most of what I learned. Calculus and even geometry just aren’t something I use in my current every-day life. In these chapters, the authors work though some of Archimedes’ logic and proofs. At first I thought I’d just skim or skip them, but found myself drawn in, working carefully through the text, and remembering doing the same thing as a student. And I was quite captivated by the “stomachion,” a puzzle that Archimedes talks about where the 14 shapes in the first square to the left are rearranged to make another square (the next 2 squares are rearrangments; Archimedes wanted to know how many such rearrangements there are). I found the design really pleasing to look at. You can see all the permutations here.

![]() The book reads like a good mystery, and while quite enjoyable and engrousing, it unfortunately has very sloppy copy editing and proof reading (misplaced commas, extra words in sentences). And the two authors alternate chapters, but don’t tell you ahead of time who’s writing, leaving this reader confused.

The book reads like a good mystery, and while quite enjoyable and engrousing, it unfortunately has very sloppy copy editing and proof reading (misplaced commas, extra words in sentences). And the two authors alternate chapters, but don’t tell you ahead of time who’s writing, leaving this reader confused.

![]() There’s a nice overview article about the palimpsest and the project from the New York Times here. The project itself has a very informative website, with videos as well as text. It might be better than reading the book.

There’s a nice overview article about the palimpsest and the project from the New York Times here. The project itself has a very informative website, with videos as well as text. It might be better than reading the book.

It’s calendar-buying season, and as usually happens, I can’t decide on the optimum system for keeping track of stuff next year. Of course I have the desktop calendar I designed and printed, but it’s for viewing only, not writing appointments and notes. I used to have a Palm Pilot and was good about keeping it up-to-date. But after changing and upgrading computers enough times, it’s no longer compatible with anything I currently own. I’ve tried various paper planner systems, all of which I abandon before March 1. Last year I bought a thick one-page-a-day book, but it’s too heavy and bulky and I can’t see far enough ahead. I replaced it with a month-by-month version that I print on my laser printer, but I have trouble disciplining myself to write everything in (hence the pile of appointment cards and random slips of paper on my desk that I force myself to go through periodically so I don’t miss anything).

It’s calendar-buying season, and as usually happens, I can’t decide on the optimum system for keeping track of stuff next year. Of course I have the desktop calendar I designed and printed, but it’s for viewing only, not writing appointments and notes. I used to have a Palm Pilot and was good about keeping it up-to-date. But after changing and upgrading computers enough times, it’s no longer compatible with anything I currently own. I’ve tried various paper planner systems, all of which I abandon before March 1. Last year I bought a thick one-page-a-day book, but it’s too heavy and bulky and I can’t see far enough ahead. I replaced it with a month-by-month version that I print on my laser printer, but I have trouble disciplining myself to write everything in (hence the pile of appointment cards and random slips of paper on my desk that I force myself to go through periodically so I don’t miss anything).

![]() At the Pyramid Atlantic Book Fair, I found a 3 x 6 x 1/4 inch day planner with month and week views, covered with marbled paper by Chena River Marblers (that’s the paper above). The paper makes me very happy. The size is just right for my purse (although it may get lost on my messy desk). But my current thought is that by picking something that I like to look at, I’ll use it. I’ll report back in March! (In the meantime, take a look at Chena River’s gorgeous papers.)

At the Pyramid Atlantic Book Fair, I found a 3 x 6 x 1/4 inch day planner with month and week views, covered with marbled paper by Chena River Marblers (that’s the paper above). The paper makes me very happy. The size is just right for my purse (although it may get lost on my messy desk). But my current thought is that by picking something that I like to look at, I’ll use it. I’ll report back in March! (In the meantime, take a look at Chena River’s gorgeous papers.)