For an upcoming issue of Ampersand (a quarterly journal I edit), I’ve asked half a dozen book artists to comment on the role of craft in their work. This article grew out of the exhibit New West Coast Design at the San Francisco Center for the Book that emphasised the technical expertise required in creating artists’ books.

For an upcoming issue of Ampersand (a quarterly journal I edit), I’ve asked half a dozen book artists to comment on the role of craft in their work. This article grew out of the exhibit New West Coast Design at the San Francisco Center for the Book that emphasised the technical expertise required in creating artists’ books.

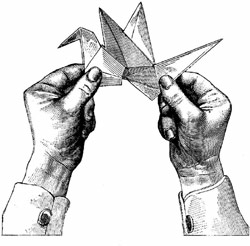

![]() This past weekend, as I set about to write an introduction to the article, I thought about what craft means for me. First I hit the dictionary: Craft: an art, trade, or occupation requiring special skill, especially manual skill. It’s a very old word — the dictionary dates its origin to before 900 AD. Today the emphasis seems to be on the manual skill part of the definition, arising from the Arts and Crafts movement of the late 19th century, a style that was a reaction to the “soulless” machine-made production of the Industrial Revolution. For book artists, the wide range of skills involved in making a book can be daunting: a handmade book might include paper making, typography, a range of illustration and printmaking techniques, calligraphy, not to mention those of bookbinding itself.

This past weekend, as I set about to write an introduction to the article, I thought about what craft means for me. First I hit the dictionary: Craft: an art, trade, or occupation requiring special skill, especially manual skill. It’s a very old word — the dictionary dates its origin to before 900 AD. Today the emphasis seems to be on the manual skill part of the definition, arising from the Arts and Crafts movement of the late 19th century, a style that was a reaction to the “soulless” machine-made production of the Industrial Revolution. For book artists, the wide range of skills involved in making a book can be daunting: a handmade book might include paper making, typography, a range of illustration and printmaking techniques, calligraphy, not to mention those of bookbinding itself.

![]() In my ramble through my bookshelf and on the internet, I found 2 quotes about craftsmanship that I especially like. The first is from the curators’ statement for the exhibit at SFCB. It’s by Leonard Koren, from 13 Books (notes on the design, construction & marketing of my last . . . ) Stone Bridge Press, Berkeley, California, 2001

In my ramble through my bookshelf and on the internet, I found 2 quotes about craftsmanship that I especially like. The first is from the curators’ statement for the exhibit at SFCB. It’s by Leonard Koren, from 13 Books (notes on the design, construction & marketing of my last . . . ) Stone Bridge Press, Berkeley, California, 2001

“I want to present . . . as perfect an object as I can. What it could have been, or should have been, is irrelevant. As the creator, I have the ultimate responsibility to make sure my books are produced according to my conception. . . . The problem with bad craftsmanship is that it needlessly distracts from the purity of your communication; it draws away energy and attention; it raises more questions in the reader’s mind that shouldn’t be there.”

The other, by way of my friend Cathy, is from David Pye’s book The Nature and Art of Workmanship, Cambridge University Press, 1968

“If I must ascribe a meaning to the word craftsmanship, I shall say as a first approximation that it means simply workmanship using any kind of technique or apparatus, in which the quality of the result is not predetermined, but depends on the judgement, dexterity and care which the maker exercises as he works. The essential idea is that the quality of the result is continually at risk during the process of making; and so I shall call this kind of workmanship ‘The workmanship of risk’: an uncouth phrase, but at least descriptive.”

I’ll be eager to see The Ampersand article!

In rambling through the New York Review of Book yesterday, I came across a little ad for a book called The Craftsman, by Richard Sennett, and the description that I found online speaks to the issues you’ve raised:

“Craftsmanship names the basic human impulse to do a job well for its own sake, says the author, and good craftsmanship involves developing skills and focusing on the work rather than ourselves. In this thought-provoking book, one of our most distinguished public intellectuals explores the work of craftsmen past and present, identifies deep connections between material consciousness and ethical values, and challenges received ideas about what constitutes good work in today’s world.

“The Craftsman engages the many dimensions of skill—from the technical demands to the obsessive energy required to do good work. Craftsmanship leads Sennett across time and space, from ancient Roman brickmakers to Renaissance goldsmiths to the printing presses of Enlightenment Paris and the factories of industrial London; in the modern world he explores what experiences of good work are shared by computer programmers, nurses and doctors, musicians, glassblowers, and cooks. Unique in the scope of his thinking, Sennett expands previous notions of crafts and craftsmen and apprises us of the surprising extent to which we can learn about ourselves through the labor of making physical things.”