Originally from here — I have had a lot of problems getting all the pages to display on that link, so here’s the text in its entirety.

Van Vliet’s Rocks

by Bob Bahr

January 31 2006

Claire Van Vliet, a veteran printmaker and an acclaimed art-book printer and publisher, loves to draw rocks. “Drawing rocks gives you a really good excuse to make a picture that is just pure form, without a literal history,” she says. “When I start, the form catches my imagination — the shape of the rock is what catches my eye. I’m not looking for anything specific. That’s why I like to work with something abstract like a rock. I’m just looking, seeing.”

The artist visits notable rock formations wherever her job takes her. Friends know to plan outings to areas with visually striking rocks when Van Vliet comes to their part of the world, be it New Zealand, New Mexico, or New England. Once she has explored the landscape, she can give the stones in her lithographs, graphite and ink drawings, vitreographs, and engravings the dignity and monumentality that these millenniums-old subjects deserve.

Her work achieves an exquisite balance between detailed depiction and artful suggestion. The rock formations and mountains in her art dominate the landscape, sometimes suggesting an otherworldly scene, sometimes a view that seems extremely familiar. The artist seeks to convey the emotions the rocks provoke in her. “I’m not very interested in expressing myself. I just want my work to invite me to feel a certain way — or invite me to fantasize. Ideally, it will have the same effect on other viewers too. I want the viewer to respond emotionally and visually to the work without engaging the part of the brain that is dismissive, that catalogs and categorizes, which I think gets in the way of direct visual communication.”

Not all artists make a rock or rock formation the focal point of a piece, but nearly everyone will include rocks in a work at some point. Van Vliet has some tips for them: “It’s always a good idea to know your subject. So move around it,” she says. “You don’t want to be a copyist. You want to know where the rock is going when it leaves your view — keep in mind that all of the edges are totally arbitrary based on your vantage point.” Van Vliet also recommends a trick that’s been around since medieval times: To depict a mountain, put a jagged rock on your drawing desk and draw it as a mountain. If one wants to delve deeper into the depiction of rocks, as Van Vliet has, then the questions really begin to flow.

“Ask yourself why the rock has taken this form,” she says. “What has made it this way? When you get involved with that, you get involved with a story, and then you get involved with tension. You’ll see areas on the rock where there are places laid bare by the elements, and other places the elements have swirled around and made some sort of secret cave. What’s the story? Ask the simplest questions you can think of.”

Her pursuit of the story in rocks has led the artist very far — and close to home. In 1989, Van Vliet was named a MacArthur Foundation Fellow for her role in starting Janus Press. She used part of the money to visit the rocks in Abiquiu, New Mexico, that inspired Georgia O’Keeffe and countless other artists. And although her depictions of the unusual boulders in Moeraki, New Zealand, constitute some of her most captivating work, she has found powerful inspiration very near to her Vermont home. Wheeler Mountain, near Willoughby Lake, so intrigued Van Vliet that she embarked on a large series of prints, drawings, and paintings titled Toward Ninety-Nine Views of Wheeler Mountain. “It’s what is called a whaleback mountain, a rather normal rock formation up here that is formed by glaciers,” she explains. “Whaleback mountains are smoothed off on the top, with a radical drop on one of the sides. Every angle you see them from makes them appear very, very different.”

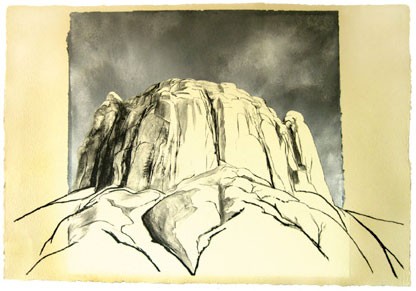

One of Van Vliet’s lithographs of stones, entitled Ghost Mesa, is of the rocks near Abiquiu, New Mexico

Van Vliet switches from vitreographs (which use etched glass plates) to lithographs to ink drawings to watercolors with ease. The characteristics of the rock suggest the medium. “The litho is a drawing medium, so if there is more softness and complexity in the shapes, that is much more easily done on the stone. And, of course, I love to draw stone on stone,” she says with a laugh. “Compare it to vitreography. In that medium, you can’t reverse anything, because the glass is tough. Every mark you make cannot be lightened. You have to plan it out in a much more careful way; lithos are much more spontaneous. But the vitreograph allows such a rich black next to fine white lines, so vitreography is really perfect for something like the Moeraki Boulders, for getting all those luscious blacks. If you stare at the Moeraki Boulders vitreographs for a while, your eye starts suggesting that the moonlight is actually moving down to them. Your eye and the black just do it. If the black were reflective in any way, I don’t think it would work.” Van Vliet points out that she is not merely illustrating the scenes she sees. For example, she never saw the Moeraki Boulders at night. The nocturnal vitreographs of the boulders were done from imagination.

Indeed, the artist’s approach runs the gamut from detailed on-site drawings that culminate in intricate prints, to works pulled largely from imagination, with just a few rough sketches as guides. Detailed drawings allow her to work out and avoid drawing problems before she is working on a plate for a print. But she shuns detailed drawings for pieces where she has a “more emotional response to the form.” That includes all her lithos. When Van Vliet works from photographs, she pairs the photos with rough drawings to get the spontaneity she desires — the sense of the place. “I have done some very descriptive drawings,” she says. “But often I won’t have time to do a detailed drawing, or the weather doesn’t permit it. I’ll take maybe 36 photos of a rock, walking around it. The cast shadows are not something that I am interested in — they usually just indicate that someone is working from a photograph.”

“I’m not literally illustrating the place,” she reiterates. “The drawing is trying to understand the natural world. But once I make the first mark on the plate or stone, the print takes over. The preliminary drawing becomes background information, research. My prints are usually not very carefully drawn out at first. I want a feeling of uncertainty when I am working on the actual print.”

And if the results don’t satisfy her, Van Vliet feels free to improvise. Several pieces by the artist feature a print affixed to a larger piece of paper, with drawn lines continuing the composition of the print. These collages are not so much a mistake on the part of the artist as they are a result of overzealousness. “They started with drawings on litho stones of finite size,” Van Vliet recalls. “We printed a 22-inch paper on a 24″-x-36” stone so that the drawing went off the paper. I collaged it onto a larger piece of paper and, with printer’s ink, drew beyond the print. I was just trying to free up what was a cramped lithograph.

“I have a tendency to fill up the litho stone,” she explains. “Once, when given the option of using one stone for experimentation and a second one to draw a litho, I instead made a diptych. Artists will always take up all the space there is,” Van Vliet says with a hearty laugh. “A long time ago I decided that I can’t have a bigger studio, because I will just make even bigger work. Then I’d still have a space problem!”