To help me in my search for poetry in every day life, David Brooks wrote a column just for me: Poetry for Everyday Life. He elaborates on the idea of “pedestrian poetry” from Steven Pinker’s book How the Mind Works. Pinker writes that in our speaking we use “everyday metaphors that express the bulk of our experiences.” For instance:

To help me in my search for poetry in every day life, David Brooks wrote a column just for me: Poetry for Everyday Life. He elaborates on the idea of “pedestrian poetry” from Steven Pinker’s book How the Mind Works. Pinker writes that in our speaking we use “everyday metaphors that express the bulk of our experiences.” For instance:

Ideas are Food:

What he said left a bad taste in my mouth.

All this paper has are half-baked ideas and warmed-over theories.

I can’t swallow that claim.

Brooks basically says we are all poets and don’t know it:

Most of us, when asked to stop and think about it, are by now aware of the pervasiveness of metaphorical thinking. But in the normal rush of events, we often see straight through metaphors, unaware of how they refract perceptions. So it’s probably important to pause once a month or so to pierce the illusion that we see the world directly. It’s good to pause to appreciate how flexible and tenuous our grip on reality actually is.

Metaphors help compensate for our natural weaknesses. Most of us are not very good at thinking about abstractions or spiritual states, so we rely on concrete or spatial metaphors to (imperfectly) do the job. A lifetime is pictured as a journey across a landscape. A person who is sad is down in the dumps, while a happy fellow is riding high.

Most of us are not good at understanding new things, so we grasp them imperfectly by relating them metaphorically to things that already exist.

Reading some of the comments to Brooks’ column, I discovered Robert Frost’s 1931 talk delivered at Amherst College Education by Poetry, where he says much the same as Pinker & Brooks. Frost says “Education by poetry is education by metaphor.” and then

Poetry begins in trivial metaphors, pretty metaphors, “grace” metaphors, and goes on to the profoundest thinking that we have. Poetry provides the one permissible way of saying one thing and meaning another. People say, “Why don’t you say what you mean?” We never do that, do we, being all of us too much poets. We like to talk in parables and in hints and in indirections—whether from diffidence or some other instinct.

Certainly metaphors can be trite as well as ridiculous and laughable (just listen to most politicians), but I’m going to listen to my friends a bit differently this week, as if they are all poets.

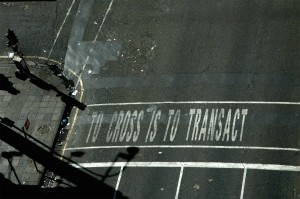

![]() {The photo with this post is taken from this blog post about a collection of six painted street crossings in central Johannesburg, done in 2007.}

{The photo with this post is taken from this blog post about a collection of six painted street crossings in central Johannesburg, done in 2007.}