This shelf is cast entirely in bone china with a working f-clamp that opens and closes…

The short version: Archimedes is considered one of the greatest mathematicians of all time. He died in 212 BC. He wrote his thoughts and proofs in Greek on papyrus rolls and sent them as letters to other mathematicians. Over time these ideas were preserved both by being translated (into Latin and Arabic) and rewritten (by scribes into the codex book form). Little of the Greek original remains today, in any form, and much of what he wrote is presumed lost. One rare codex that contains the original Greek is the The Archimedes Palimpsest. A palimpsest is a parchment text where the writing has been partially or completely erased and another text written over it. The Archimedes Palimpsest outwardly looks like a medieval prayer book from the 13th century, the text that was erased and overwritten by the prayers is a transcription of several of Archimedes’ letters. The book is in horrible shape — full of mold, with pages lost or cut out, and very bad mending. In 1998 an anonymous collector bought the book and since then it has gone through another transformation — conservation and digital imaging to allow scholars to read Archimedes’ text. The Archimedes Codex tells the story of the codex and what was found in reading the texts.

The short version: Archimedes is considered one of the greatest mathematicians of all time. He died in 212 BC. He wrote his thoughts and proofs in Greek on papyrus rolls and sent them as letters to other mathematicians. Over time these ideas were preserved both by being translated (into Latin and Arabic) and rewritten (by scribes into the codex book form). Little of the Greek original remains today, in any form, and much of what he wrote is presumed lost. One rare codex that contains the original Greek is the The Archimedes Palimpsest. A palimpsest is a parchment text where the writing has been partially or completely erased and another text written over it. The Archimedes Palimpsest outwardly looks like a medieval prayer book from the 13th century, the text that was erased and overwritten by the prayers is a transcription of several of Archimedes’ letters. The book is in horrible shape — full of mold, with pages lost or cut out, and very bad mending. In 1998 an anonymous collector bought the book and since then it has gone through another transformation — conservation and digital imaging to allow scholars to read Archimedes’ text. The Archimedes Codex tells the story of the codex and what was found in reading the texts.

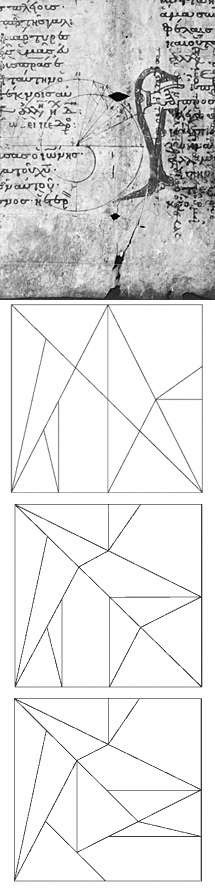

![]() The chapters in the book alternate between the story of the physical object and the story of reading the texts contained in the codex. My original interest was in the conservation effort, and while there’s certainly a lot of that, I got much more. For example there’s a discussion of the “technology changes” in reading and writing between third century BC and now. Archimedes wrote in uppercase Greek with no word spaces — just thinking about reading an all uppercase text gives me a headache, so I can’t imagine reading something with no word spaces. Conserving the book also meant taking pictures of the pages, and if possible, making the underlying Archimedes text legible. The second half of the book details that effort, which surprisingly involved using Stanford’s linear accelerator to image and get to some of the text that was covered over by thick layers of paint. The photo at the upper left shows one page of the book, with a diagram from Archimedes showing up faintly in the background. To the right you can see the Greek under the Latin prayer text and pointing hand.

The chapters in the book alternate between the story of the physical object and the story of reading the texts contained in the codex. My original interest was in the conservation effort, and while there’s certainly a lot of that, I got much more. For example there’s a discussion of the “technology changes” in reading and writing between third century BC and now. Archimedes wrote in uppercase Greek with no word spaces — just thinking about reading an all uppercase text gives me a headache, so I can’t imagine reading something with no word spaces. Conserving the book also meant taking pictures of the pages, and if possible, making the underlying Archimedes text legible. The second half of the book details that effort, which surprisingly involved using Stanford’s linear accelerator to image and get to some of the text that was covered over by thick layers of paint. The photo at the upper left shows one page of the book, with a diagram from Archimedes showing up faintly in the background. To the right you can see the Greek under the Latin prayer text and pointing hand.

![]() The alternating chapters tell what was found in the texts and how they were read and interpreted. Here’s where I got my biggest surprise. I majored in math in college, but that was a long time ago and I’ve forgotten most of what I learned. Calculus and even geometry just aren’t something I use in my current every-day life. In these chapters, the authors work though some of Archimedes’ logic and proofs. At first I thought I’d just skim or skip them, but found myself drawn in, working carefully through the text, and remembering doing the same thing as a student. And I was quite captivated by the “stomachion,” a puzzle that Archimedes talks about where the 14 shapes in the first square to the left are rearranged to make another square (the next 2 squares are rearrangments; Archimedes wanted to know how many such rearrangements there are). I found the design really pleasing to look at. You can see all the permutations here.

The alternating chapters tell what was found in the texts and how they were read and interpreted. Here’s where I got my biggest surprise. I majored in math in college, but that was a long time ago and I’ve forgotten most of what I learned. Calculus and even geometry just aren’t something I use in my current every-day life. In these chapters, the authors work though some of Archimedes’ logic and proofs. At first I thought I’d just skim or skip them, but found myself drawn in, working carefully through the text, and remembering doing the same thing as a student. And I was quite captivated by the “stomachion,” a puzzle that Archimedes talks about where the 14 shapes in the first square to the left are rearranged to make another square (the next 2 squares are rearrangments; Archimedes wanted to know how many such rearrangements there are). I found the design really pleasing to look at. You can see all the permutations here.

![]() The book reads like a good mystery, and while quite enjoyable and engrousing, it unfortunately has very sloppy copy editing and proof reading (misplaced commas, extra words in sentences). And the two authors alternate chapters, but don’t tell you ahead of time who’s writing, leaving this reader confused.

The book reads like a good mystery, and while quite enjoyable and engrousing, it unfortunately has very sloppy copy editing and proof reading (misplaced commas, extra words in sentences). And the two authors alternate chapters, but don’t tell you ahead of time who’s writing, leaving this reader confused.

![]() There’s a nice overview article about the palimpsest and the project from the New York Times here. The project itself has a very informative website, with videos as well as text. It might be better than reading the book.

There’s a nice overview article about the palimpsest and the project from the New York Times here. The project itself has a very informative website, with videos as well as text. It might be better than reading the book.

It’s calendar-buying season, and as usually happens, I can’t decide on the optimum system for keeping track of stuff next year. Of course I have the desktop calendar I designed and printed, but it’s for viewing only, not writing appointments and notes. I used to have a Palm Pilot and was good about keeping it up-to-date. But after changing and upgrading computers enough times, it’s no longer compatible with anything I currently own. I’ve tried various paper planner systems, all of which I abandon before March 1. Last year I bought a thick one-page-a-day book, but it’s too heavy and bulky and I can’t see far enough ahead. I replaced it with a month-by-month version that I print on my laser printer, but I have trouble disciplining myself to write everything in (hence the pile of appointment cards and random slips of paper on my desk that I force myself to go through periodically so I don’t miss anything).

It’s calendar-buying season, and as usually happens, I can’t decide on the optimum system for keeping track of stuff next year. Of course I have the desktop calendar I designed and printed, but it’s for viewing only, not writing appointments and notes. I used to have a Palm Pilot and was good about keeping it up-to-date. But after changing and upgrading computers enough times, it’s no longer compatible with anything I currently own. I’ve tried various paper planner systems, all of which I abandon before March 1. Last year I bought a thick one-page-a-day book, but it’s too heavy and bulky and I can’t see far enough ahead. I replaced it with a month-by-month version that I print on my laser printer, but I have trouble disciplining myself to write everything in (hence the pile of appointment cards and random slips of paper on my desk that I force myself to go through periodically so I don’t miss anything).

![]() At the Pyramid Atlantic Book Fair, I found a 3 x 6 x 1/4 inch day planner with month and week views, covered with marbled paper by Chena River Marblers (that’s the paper above). The paper makes me very happy. The size is just right for my purse (although it may get lost on my messy desk). But my current thought is that by picking something that I like to look at, I’ll use it. I’ll report back in March! (In the meantime, take a look at Chena River’s gorgeous papers.)

At the Pyramid Atlantic Book Fair, I found a 3 x 6 x 1/4 inch day planner with month and week views, covered with marbled paper by Chena River Marblers (that’s the paper above). The paper makes me very happy. The size is just right for my purse (although it may get lost on my messy desk). But my current thought is that by picking something that I like to look at, I’ll use it. I’ll report back in March! (In the meantime, take a look at Chena River’s gorgeous papers.)

My Reader’s Diary was mentioned recently in a blog article by Sarah Nicholls of the Center for Book Arts in NYC. Top 10 Books, Zines & Comics is a good introduction to what’s on offer on Etsy. She lists 10 categories (zines, comics, diaries, journals, albums, letterpress books….) with an example of each and then a link to search for more. Check it out here. The one to the left is the zine “Stastictical Analysis of The Things That Happen But Don’t Matter” from Sarah McNeil.

My Reader’s Diary was mentioned recently in a blog article by Sarah Nicholls of the Center for Book Arts in NYC. Top 10 Books, Zines & Comics is a good introduction to what’s on offer on Etsy. She lists 10 categories (zines, comics, diaries, journals, albums, letterpress books….) with an example of each and then a link to search for more. Check it out here. The one to the left is the zine “Stastictical Analysis of The Things That Happen But Don’t Matter” from Sarah McNeil.

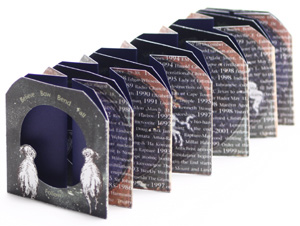

Several years ago my friend Debbie gave me a copy of Tara Bryan’s tunnel book, World Without End (that’s it to the right). A tunnel or peephole book is a set of pages bound into accordions on two sides and viewed through a central opening. Scenery or shapes are cut out of the pages and then assembled in layers. Inspired by theatrical stage sets, this book form dates from the mid-eighteenth century and continues to be popular. I immediately deconstructed Tara’s book to figure out how she made it (very ingeniously with a single sheet of paper) and then wrote up instructions for a class I was teaching at SFCB.

Several years ago my friend Debbie gave me a copy of Tara Bryan’s tunnel book, World Without End (that’s it to the right). A tunnel or peephole book is a set of pages bound into accordions on two sides and viewed through a central opening. Scenery or shapes are cut out of the pages and then assembled in layers. Inspired by theatrical stage sets, this book form dates from the mid-eighteenth century and continues to be popular. I immediately deconstructed Tara’s book to figure out how she made it (very ingeniously with a single sheet of paper) and then wrote up instructions for a class I was teaching at SFCB.

![]() For the Fall 2008 Ampersand, Debbie wrote a profile of Tara, and I thought I’d include those instructions in the issue as well. Then John Sullivan, who is the new president of PCBA (the member organization that publishes Ampersand), cut and scored sheets with a blank tunnel book on it, so members could easily make their own. You can buy a copy of the Fall Ampersand here.

For the Fall 2008 Ampersand, Debbie wrote a profile of Tara, and I thought I’d include those instructions in the issue as well. Then John Sullivan, who is the new president of PCBA (the member organization that publishes Ampersand), cut and scored sheets with a blank tunnel book on it, so members could easily make their own. You can buy a copy of the Fall Ampersand here.

![]() Ed Hutchins’ article Exploring Tunnel Books includes a history of tunnel books and a photo gallery of example books. There are good discussions of what makes the structure a book, rather than a novelty piece, how various artists have adapted the form, and how one might incorporate text.

Ed Hutchins’ article Exploring Tunnel Books includes a history of tunnel books and a photo gallery of example books. There are good discussions of what makes the structure a book, rather than a novelty piece, how various artists have adapted the form, and how one might incorporate text.

![]() Book artist and teacher Carol Barton has been instrumental in popularizing tunnel books with book artists. You can see some of her early work, along with several other artists’ examples.

Book artist and teacher Carol Barton has been instrumental in popularizing tunnel books with book artists. You can see some of her early work, along with several other artists’ examples.

![]() Maria Pisano’s The Four Elements Series are elegant miniature tunnel books (scroll down on the page to see them). There are good pictures of each book, allowing you to see inside as well as how she made the covers. There’s another tunnel book on that page too, called Tunnel Vision.

Maria Pisano’s The Four Elements Series are elegant miniature tunnel books (scroll down on the page to see them). There are good pictures of each book, allowing you to see inside as well as how she made the covers. There’s another tunnel book on that page too, called Tunnel Vision.

![]() Peter & Donna Thomas have made a tunnel book inside a ukulele. They have more traditional tunnel books pictured here and here.

Peter & Donna Thomas have made a tunnel book inside a ukulele. They have more traditional tunnel books pictured here and here.

Judith Hollowood sent me a postcard with this great sculpture on the front — it’s called Headwaters by Larry Kirkland. It sits in front of the English/Philosophy complex on the Lubbock campus of Texas Tech University. (There’s another good picture here on flickr.) Texas Tech & Lubbock have amassed quite a public art collection.

Judith Hollowood sent me a postcard with this great sculpture on the front — it’s called Headwaters by Larry Kirkland. It sits in front of the English/Philosophy complex on the Lubbock campus of Texas Tech University. (There’s another good picture here on flickr.) Texas Tech & Lubbock have amassed quite a public art collection.