Recently on the book arts listserv, someone posted a link to the “bookbinding press” to the left — sold at Restoration Hardware as “a faithful reproduction of a century-old bookbinder’s press, used to keep even pressure on books as they dried” and “hefty enough to double as a bookend, and useful for pressing forget-me-nots between pages as well.” Someone responded that this was “copy press” not a “book press,” which started a conversation about the difference between the two.

Recently on the book arts listserv, someone posted a link to the “bookbinding press” to the left — sold at Restoration Hardware as “a faithful reproduction of a century-old bookbinder’s press, used to keep even pressure on books as they dried” and “hefty enough to double as a bookend, and useful for pressing forget-me-nots between pages as well.” Someone responded that this was “copy press” not a “book press,” which started a conversation about the difference between the two.

My understanding is the main difference between a copy press and a book press is the amount of daylight between the platen and the base. My press has only 3-1/2″ daylight which is fine for a single book. Book presses have

at least 12″ of space so they can accommodate more than one book in the press.

David Amstell piped in

It would seem that there is a difference between a Copy Press and a Bookbinder’s Press… The central screw of the true bookbinder’s press has a thread with a considerably lower slope. This means that when the press is tightened up, the wheel or T-bar can be given an extra distance of tightening, thus providing extra pressure to the book. On the other hand, the platen of many copy presses, which usually have a higher screw slope, bounce back slightly from the full tightening, thus giving an inefficient pressing…The manufacturers of some of the modern bookbinding presses, it would appear, have realised this principle of the low-angled screw. Consequently, their presses are very efficient to use.

But what exactly is a “copy press?” Several people on the listserv mentioned an out-of-print book “Before Photocopying: The Art And History Of Mechanical Copying 1780-1938” by Barbara J. Rhodes and William W. Streeter (Hardcover – May 1999), but didn’t explain. So I looked online and found 2 things: Thomas Jefferson’s design for a portable copying press was first built in London in 1786, see a picture here and more about it here. And in this nice post about Richard Bell’s research into the history of a copy press he got from his father, he clears up the difference with this:

In an article published in The Office magazine about Victorian desktop publishing, Darryl Rherr writes:

“Desktop Publishing’s first century began in 1856, when British chemist William Perkins discovered the first synthetic dye, aniline purple. This dye pointed the way to a wide range of new inks, including ‘copying ink’ used in the first practical method of reproducing business documents.

An original written with copying ink was placed against a moistened sheet of tissue, the two were pressed together in a massive iron press, and a copy would appear on the tissue. Since the copy was backwards, the tissue had to be held up to the light to be read. The copy press became a fixture in every Victorian office. Today, they are sold in antique shops as ‘book presses,’ their true function long forgotten.”

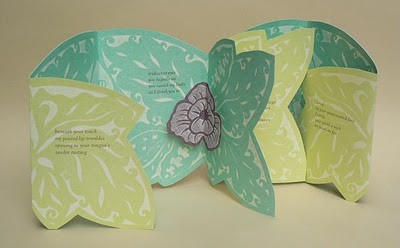

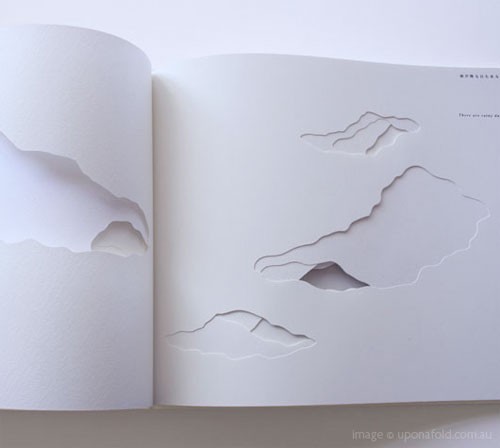

Many of my friends remember their first book arts classes very fondly — especially my friend Sharon. She took a class with Daniel Kelm that involved rivets and other metal closures and binding methods. My first class was with Kumi Korf, and I often return to the books I made in her classes for a jolt of inspiration.

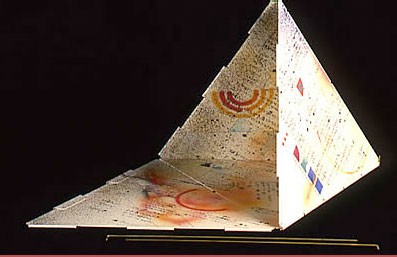

Many of my friends remember their first book arts classes very fondly — especially my friend Sharon. She took a class with Daniel Kelm that involved rivets and other metal closures and binding methods. My first class was with Kumi Korf, and I often return to the books I made in her classes for a jolt of inspiration.![]() Sharon recently sent me a link to an exhibition of Kelm’s work at Smith College called Poetic Science. There are lots of pictures of his binding work, including the one pictured, Capsicum Red, a collaboration with Tim Ely. His inventive bindings are always fun to look at and contemplate — especially the ones that move and can be reconfigured (there are videos of some of those, like this one here called Religio Mathmatica).

Sharon recently sent me a link to an exhibition of Kelm’s work at Smith College called Poetic Science. There are lots of pictures of his binding work, including the one pictured, Capsicum Red, a collaboration with Tim Ely. His inventive bindings are always fun to look at and contemplate — especially the ones that move and can be reconfigured (there are videos of some of those, like this one here called Religio Mathmatica).