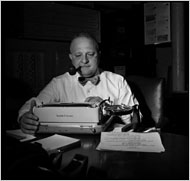

| Martin Tytell, whose unmatched knowledge of typewriters was a boon to American spies during World War II, a tool for the defense lawyers for Alger Hiss, and a necessity for literary luminaries and perhaps tens of thousands of everyday scriveners who asked him to keep their Royals, Underwoods, Olivettis (and their computer-resistant pride) intact, died on Thursday in the Bronx. He was 94….

He made a hieroglyphics typewriter for a museum curator, and typewriters with musical notes for musicians. He adapted keyboards for amputees and other wounded veterans. He invented a reverse-carriage device that enabled him to work in right-to-left languages like Arabic and Hebrew. An error he made on a Burmese typewriter, inserting a character upside down, became a standard, even in Burma….

Mr. Tytell was proud of the rarity of his expertise, and relished the eccentric nature of his business. “We don’t get normal people here,” he said of his shop. And he was aware that his connection to the typewriter bordered on love.

“I’m 83 years old and I just signed a 10-year lease on this office; I’m an optimist, obviously,” Mr. Tytell told the writer Ian Frazier in a 1997 article in The Atlantic Monthly, commenting on the likelihood that typewriters weren’t going to last in the world much longer. “I hope they do survive — manual typewriters are where my heart is. They’re what keep me alive.”

Don’t miss Ian Frazier’s article about his search to fix the errant “e” on his beloved manual typewriter that lead him to Tytell — it’s a wonderful read. At the end, Mr. Tytell says:

“What’s so intriguing about a manual typewriter is that it’s all right there in front of you — all the thought that went into it, all these really smart guys that worked on it and gave their lives for it. The way these machines continue to function, it really is a miracle. You see some old beat-up machine in an attic or someplace and you touch the keys and it still works fine. Companies still make typewriter ribbons — the dry-goods business is as strong as ever — so obviously somebody’s still using them. Like in the war, nobody was making typewriters, but people kept on using them anyway. A little bit of maintenance and regular use and you can keep a typewriter running a long time. These other machines, computers and so on, even electric typewriters, they have a soul that’s hooked into the wall. A manual typewriter has a soul that doesn’t need anything else in order to exist — it exists in itself. People are always going to like that about a manual.”

(The photo above is by Patrick Burns for the NY Times.)

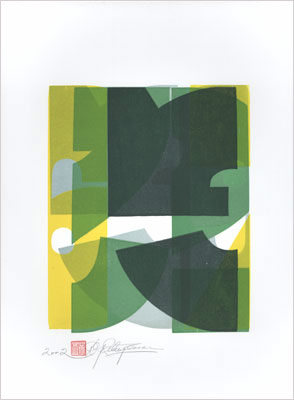

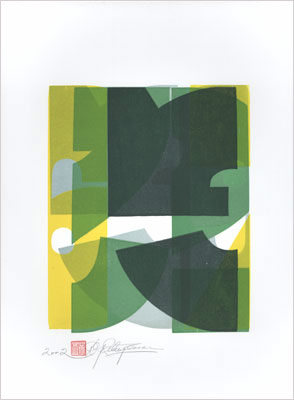

Dennis Ichiyama is a former Designer-in-Residence at the Hamilton Wood Type and Printing Museum and currently Professor of Art and Design at Purdue University. Of his experiments with pieces of broken wood type and lead rules, he says “I’m just picking letters and colors and playing with them.” To create his prints, he starts with 25 sheets of paper and then layers colors on top. “When I get tired, when I don’t know what else to do, I stop,” he says. “And by the time I’m done, I usually end up with about 15 that I think are good.” That’s one of Ichiyama’s prints to the left. You can see lots more here. (First seen on Colour Lovers Blog) Dennis Ichiyama is a former Designer-in-Residence at the Hamilton Wood Type and Printing Museum and currently Professor of Art and Design at Purdue University. Of his experiments with pieces of broken wood type and lead rules, he says “I’m just picking letters and colors and playing with them.” To create his prints, he starts with 25 sheets of paper and then layers colors on top. “When I get tired, when I don’t know what else to do, I stop,” he says. “And by the time I’m done, I usually end up with about 15 that I think are good.” That’s one of Ichiyama’s prints to the left. You can see lots more here. (First seen on Colour Lovers Blog)

I’ve tried letterpress printing on lots of things — from the usual paper to thick coasters to book cloth to moleskine journals, and all the way to metal and wood. But I haven’t tried fabric yet. Piano Nobile over on Etsy makes these fabric totes, letterpress printed using wood type. My press doesn’t print a large enough area to cover fabric for a big tote, so I’ll just have to buy one of their bags! (But I’m also sure I’ll soon dream up a project that involves fabric!) You can see more of their textile prints on their website.

The Winter 2008 issue of Ampersand (the book arts journal I edit) is just out. In this issue, Sarah Whorf, who teaches printmaking at Humbolt State here in California, has written up a nifty method for printing on a modified credit card imprinter. The prints are tiny — just 2″x3″ — but it’s a great platform for learning printmaking. Marsha Shaw, a student of Sarah’s, teaches printmaking to both children and adults using these modified “knucklebusters.” She’s teaching a class for teachers at SFCB in June as part of their 2008 Summer Bookbinding Institute for K-8 Teachers and another for adults in July. The Winter 2008 issue of Ampersand (the book arts journal I edit) is just out. In this issue, Sarah Whorf, who teaches printmaking at Humbolt State here in California, has written up a nifty method for printing on a modified credit card imprinter. The prints are tiny — just 2″x3″ — but it’s a great platform for learning printmaking. Marsha Shaw, a student of Sarah’s, teaches printmaking to both children and adults using these modified “knucklebusters.” She’s teaching a class for teachers at SFCB in June as part of their 2008 Summer Bookbinding Institute for K-8 Teachers and another for adults in July.

|