The short version: Archimedes is considered one of the greatest mathematicians of all time. He died in 212 BC. He wrote his thoughts and proofs in Greek on papyrus rolls and sent them as letters to other mathematicians. Over time these ideas were preserved both by being translated (into Latin and Arabic) and rewritten (by scribes into the codex book form). Little of the Greek original remains today, in any form, and much of what he wrote is presumed lost. One rare codex that contains the original Greek is the The Archimedes Palimpsest. A palimpsest is a parchment text where the writing has been partially or completely erased and another text written over it. The Archimedes Palimpsest outwardly looks like a medieval prayer book from the 13th century, the text that was erased and overwritten by the prayers is a transcription of several of Archimedes’ letters. The book is in horrible shape — full of mold, with pages lost or cut out, and very bad mending. In 1998 an anonymous collector bought the book and since then it has gone through another transformation — conservation and digital imaging to allow scholars to read Archimedes’ text. The Archimedes Codex tells the story of the codex and what was found in reading the texts.

The short version: Archimedes is considered one of the greatest mathematicians of all time. He died in 212 BC. He wrote his thoughts and proofs in Greek on papyrus rolls and sent them as letters to other mathematicians. Over time these ideas were preserved both by being translated (into Latin and Arabic) and rewritten (by scribes into the codex book form). Little of the Greek original remains today, in any form, and much of what he wrote is presumed lost. One rare codex that contains the original Greek is the The Archimedes Palimpsest. A palimpsest is a parchment text where the writing has been partially or completely erased and another text written over it. The Archimedes Palimpsest outwardly looks like a medieval prayer book from the 13th century, the text that was erased and overwritten by the prayers is a transcription of several of Archimedes’ letters. The book is in horrible shape — full of mold, with pages lost or cut out, and very bad mending. In 1998 an anonymous collector bought the book and since then it has gone through another transformation — conservation and digital imaging to allow scholars to read Archimedes’ text. The Archimedes Codex tells the story of the codex and what was found in reading the texts.

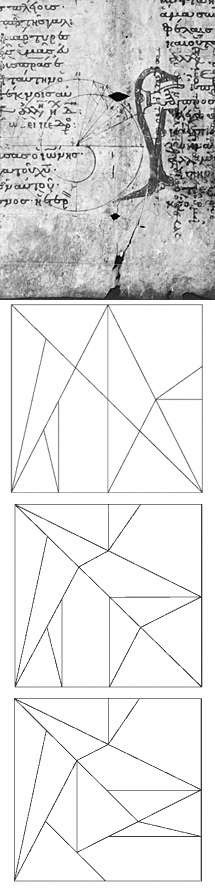

![]() The chapters in the book alternate between the story of the physical object and the story of reading the texts contained in the codex. My original interest was in the conservation effort, and while there’s certainly a lot of that, I got much more. For example there’s a discussion of the “technology changes” in reading and writing between third century BC and now. Archimedes wrote in uppercase Greek with no word spaces — just thinking about reading an all uppercase text gives me a headache, so I can’t imagine reading something with no word spaces. Conserving the book also meant taking pictures of the pages, and if possible, making the underlying Archimedes text legible. The second half of the book details that effort, which surprisingly involved using Stanford’s linear accelerator to image and get to some of the text that was covered over by thick layers of paint. The photo at the upper left shows one page of the book, with a diagram from Archimedes showing up faintly in the background. To the right you can see the Greek under the Latin prayer text and pointing hand.

The chapters in the book alternate between the story of the physical object and the story of reading the texts contained in the codex. My original interest was in the conservation effort, and while there’s certainly a lot of that, I got much more. For example there’s a discussion of the “technology changes” in reading and writing between third century BC and now. Archimedes wrote in uppercase Greek with no word spaces — just thinking about reading an all uppercase text gives me a headache, so I can’t imagine reading something with no word spaces. Conserving the book also meant taking pictures of the pages, and if possible, making the underlying Archimedes text legible. The second half of the book details that effort, which surprisingly involved using Stanford’s linear accelerator to image and get to some of the text that was covered over by thick layers of paint. The photo at the upper left shows one page of the book, with a diagram from Archimedes showing up faintly in the background. To the right you can see the Greek under the Latin prayer text and pointing hand.

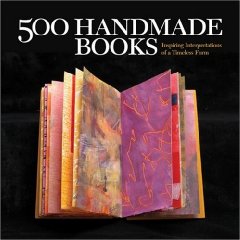

![]() The alternating chapters tell what was found in the texts and how they were read and interpreted. Here’s where I got my biggest surprise. I majored in math in college, but that was a long time ago and I’ve forgotten most of what I learned. Calculus and even geometry just aren’t something I use in my current every-day life. In these chapters, the authors work though some of Archimedes’ logic and proofs. At first I thought I’d just skim or skip them, but found myself drawn in, working carefully through the text, and remembering doing the same thing as a student. And I was quite captivated by the “stomachion,” a puzzle that Archimedes talks about where the 14 shapes in the first square to the left are rearranged to make another square (the next 2 squares are rearrangments; Archimedes wanted to know how many such rearrangements there are). I found the design really pleasing to look at. You can see all the permutations here.

The alternating chapters tell what was found in the texts and how they were read and interpreted. Here’s where I got my biggest surprise. I majored in math in college, but that was a long time ago and I’ve forgotten most of what I learned. Calculus and even geometry just aren’t something I use in my current every-day life. In these chapters, the authors work though some of Archimedes’ logic and proofs. At first I thought I’d just skim or skip them, but found myself drawn in, working carefully through the text, and remembering doing the same thing as a student. And I was quite captivated by the “stomachion,” a puzzle that Archimedes talks about where the 14 shapes in the first square to the left are rearranged to make another square (the next 2 squares are rearrangments; Archimedes wanted to know how many such rearrangements there are). I found the design really pleasing to look at. You can see all the permutations here.

![]() The book reads like a good mystery, and while quite enjoyable and engrousing, it unfortunately has very sloppy copy editing and proof reading (misplaced commas, extra words in sentences). And the two authors alternate chapters, but don’t tell you ahead of time who’s writing, leaving this reader confused.

The book reads like a good mystery, and while quite enjoyable and engrousing, it unfortunately has very sloppy copy editing and proof reading (misplaced commas, extra words in sentences). And the two authors alternate chapters, but don’t tell you ahead of time who’s writing, leaving this reader confused.

![]() There’s a nice overview article about the palimpsest and the project from the New York Times here. The project itself has a very informative website, with videos as well as text. It might be better than reading the book.

There’s a nice overview article about the palimpsest and the project from the New York Times here. The project itself has a very informative website, with videos as well as text. It might be better than reading the book.

The most satisfying bookworks I’ve produced are my “poem books.” These contain a single poem and, most important, the structure of the book and the parts used to construct it compliment the words and content. Finding the right structure is a big challenge for me, the gestation of these books is usually long and the construction can sometimes be tricky. The book that has served as the inspiration for many of my “poem books” is Elizabeth Steiner and Claire Van Vliet’s

The most satisfying bookworks I’ve produced are my “poem books.” These contain a single poem and, most important, the structure of the book and the parts used to construct it compliment the words and content. Finding the right structure is a big challenge for me, the gestation of these books is usually long and the construction can sometimes be tricky. The book that has served as the inspiration for many of my “poem books” is Elizabeth Steiner and Claire Van Vliet’s