Sociologist Richard Sennett’s The Craftsman isn’t about books or bookmaking but the larger issue of craftsmanship. It’s a flawed book in many ways, but I kept reading as it was full of thought-provoking ideas. He argues that our sense of well-being is rooted in craftsmanship and that the rewards of craftsmanship — rather than the promise of monetary gain — motivates us to work. Unfortunately our work culture isn’t hospitable to craft — the machine & money rules.

Sociologist Richard Sennett’s The Craftsman isn’t about books or bookmaking but the larger issue of craftsmanship. It’s a flawed book in many ways, but I kept reading as it was full of thought-provoking ideas. He argues that our sense of well-being is rooted in craftsmanship and that the rewards of craftsmanship — rather than the promise of monetary gain — motivates us to work. Unfortunately our work culture isn’t hospitable to craft — the machine & money rules.

For Sennett, “craftsmanship” is the basic human impulse to do a job well for its own sake. It’s certainly not unskilled manual labor, it requires the hand & head to work together (To quote Immanuel Kant: “The hand is the window on to the mind”). He also says a lot about risk: A good craftsperson “exuberant and excited, is willing to risk losing control over his or her work, machines break down when they lose control, whereas people make discoveries, stumble on happy accidents.”

For Sennett, “craftsmanship” is the basic human impulse to do a job well for its own sake. It’s certainly not unskilled manual labor, it requires the hand & head to work together (To quote Immanuel Kant: “The hand is the window on to the mind”). He also says a lot about risk: A good craftsperson “exuberant and excited, is willing to risk losing control over his or her work, machines break down when they lose control, whereas people make discoveries, stumble on happy accidents.”

To me crafts are marginalized activities — such as bookbinding — but Sennett updates this and makes the case that such professions as doctor, nurse, chiropractor, musician, and computer programmer engage in craftsmanship. All of the skills for these professions are learned and practiced today in much the same way as they were in a medieval workshop: through apprenticeships (or internships or mentors on the job), repetition, access to authority with knowledge, communities of same-skilled craftsmen.

To me crafts are marginalized activities — such as bookbinding — but Sennett updates this and makes the case that such professions as doctor, nurse, chiropractor, musician, and computer programmer engage in craftsmanship. All of the skills for these professions are learned and practiced today in much the same way as they were in a medieval workshop: through apprenticeships (or internships or mentors on the job), repetition, access to authority with knowledge, communities of same-skilled craftsmen.

Sennett makes a passionate argument that craftsmanship needs to be recognized and prized. In the current (American) culture, we seem to have bifurcated into the elites (head only) and the unskilled (hand only) — the middle-class is forgotten or ignored. Sennett deplores this, and contends that “nearly anyone can become a good craftsman” and that “learning to work well enables people to govern themselves and so become good citizens.” It’s a timely argument, given the recent financial and economic melt-down and president-elect Obama’s plans for an economic recovery program that includes rebuilding roads and infrastructure (all involving craft/hand work).

Sennett makes a passionate argument that craftsmanship needs to be recognized and prized. In the current (American) culture, we seem to have bifurcated into the elites (head only) and the unskilled (hand only) — the middle-class is forgotten or ignored. Sennett deplores this, and contends that “nearly anyone can become a good craftsman” and that “learning to work well enables people to govern themselves and so become good citizens.” It’s a timely argument, given the recent financial and economic melt-down and president-elect Obama’s plans for an economic recovery program that includes rebuilding roads and infrastructure (all involving craft/hand work).

The book is full of stories and anecdotes about the history of one craft or another. While interesting and enjoyable in themselves — they often read like a letter or blog post by a really well read guy — they too often digress from the main point. I was forever having to reorient myself as I read. And either Sennett is a horrible writer or Yale Press (who published the book) doesn’t have an editor. Not only are there typos and punctuation problems, but the language is often quite choppy and awkward. (My biggest peeve though is actually with the binding and page layout. The book is thick, the binding sewn. The gutter is so small that I had to constantly press hard on the open pages to read the rightmost words on the left page, eventually breaking the spine. Lousy craft.)

The book is full of stories and anecdotes about the history of one craft or another. While interesting and enjoyable in themselves — they often read like a letter or blog post by a really well read guy — they too often digress from the main point. I was forever having to reorient myself as I read. And either Sennett is a horrible writer or Yale Press (who published the book) doesn’t have an editor. Not only are there typos and punctuation problems, but the language is often quite choppy and awkward. (My biggest peeve though is actually with the binding and page layout. The book is thick, the binding sewn. The gutter is so small that I had to constantly press hard on the open pages to read the rightmost words on the left page, eventually breaking the spine. Lousy craft.)

Despite these flaws, I’ve been discussing the ideas and historical anecdotes with everyone I know. But I suspect a more condensed book would have gotten his ideas across just as well. The Yale Press website has several interviews with Sennett that might be a better introduction to his ideas than wading through the bad prose.

Despite these flaws, I’ve been discussing the ideas and historical anecdotes with everyone I know. But I suspect a more condensed book would have gotten his ideas across just as well. The Yale Press website has several interviews with Sennett that might be a better introduction to his ideas than wading through the bad prose.

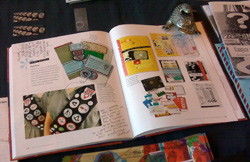

About The Oxford Companion to the Book, this review says “This colossal new encyclopaedic Companion has something to say about almost everything that matters in the world of writing, printing, publishing and book-collecting….not just the history of print, but also the history of manuscripts, libraries, bookselling and book-editing. Dozens of experts have contributed, submitting long essays on general topics or short reference entries. The result is an extraordinary tour de force, a cornucopia of bookish information.” It’s 2 volumes, 1048 pages and costs over $250 on Amazon. You can read excerpts here.

About The Oxford Companion to the Book, this review says “This colossal new encyclopaedic Companion has something to say about almost everything that matters in the world of writing, printing, publishing and book-collecting….not just the history of print, but also the history of manuscripts, libraries, bookselling and book-editing. Dozens of experts have contributed, submitting long essays on general topics or short reference entries. The result is an extraordinary tour de force, a cornucopia of bookish information.” It’s 2 volumes, 1048 pages and costs over $250 on Amazon. You can read excerpts here.

At the beginning of the year,

At the beginning of the year,